Can you spot an impostor?

If someone claiming to be your supervisor, director, or dean sent you an email from an unrecognized address with a one-word question, would you respond? These attacks are surprisingly effective, taking advantage of our trust and the way we interact with our colleagues. It’s also extremely difficult for security technologies to stop these attacks because there are no infected email attachments or malicious links to detect.

How does the attack work?

In most cases, the criminals are after money, and what makes these attacks so dangerous is the research they do prior to launching their attack. For example, if they are targeting you, they would determine the identity of your department chair or manager. Then they’ll craft a series of urgent emails pretending to be them and asking you to take an action such as wiring money, purchasing gift cards, or sending a sensitive document, always outside an established process.

Protecting yourself

Common sense is your best defense. Here are some clues to watch for if you get an email that you suspect might be from an imposter:

-

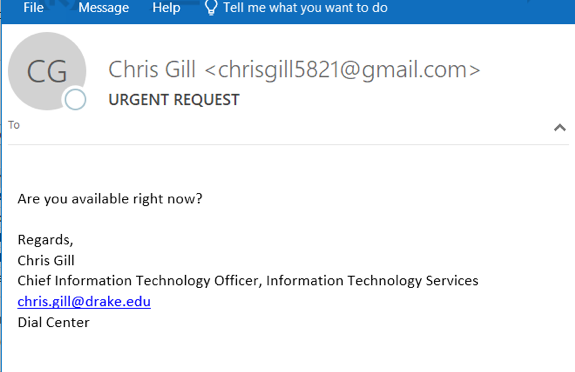

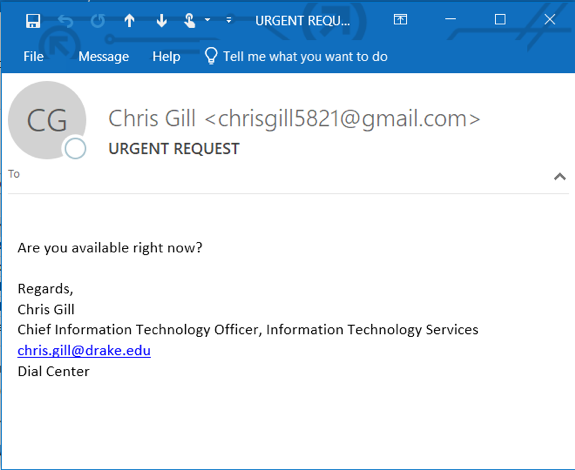

- The email will be very short (potentially just a few words).

-

- There’s a strong sense of urgency, pressuring you to ignore or bypass standard practices. You should always follow established procedures, even if the email appears to come from leadership or administration.

-

- The email is work-related but comes from a non-Drake email address, like gmail.com or hotmail.com. These emails will nearly always have an [External Email] label.

-

- The email appears to come from a leader, co-worker, or vendor you know or work with, but the tone seems different.

-

- Payment instructions are provided, but differ from ones you may have already received, such as payment to a different bank account.

If you receive a request that appears to be from an impostor, stop all interaction with them and report the message by emailing it to informationsecurity@drake.edu or submitting a request at service.drake.edu/its. ITS will continue to provide phishing education in June using emails that simulate real attacks.

—Peter Lundstedt, IT Communications

Here’s what an attack targeting ITS might look like